The following remarks were made at a presentation at Quiltcon 2019 on February 21 in Nashville, Tennessee, in conjunction with a special exhibit of my quilts. This presentation concluded with a few additional slides of quilts, and in giving the talk I riffed on what is written here. In all, 23 quilts were exhibited at the convention. Thanks to Rita Heisey, Susan Watson, and Hilari Oller for their help refining my presentation.

When I first heard how many people had registered for my presentation, I was pretty nervous. But then I quickly remembered my audience would be full of quilt lovers. Like me. I’m a quilt lover, not an academic or quilt maker. My name is Marjorie Childress, a nerdy quilt fan girl out in New Mexico who collects antique and vintage quilts.

I adopted the moniker “anonymous quilt” as a framing term for my collection, because the vast majority of vintage and antique quilts are unsigned and undated.

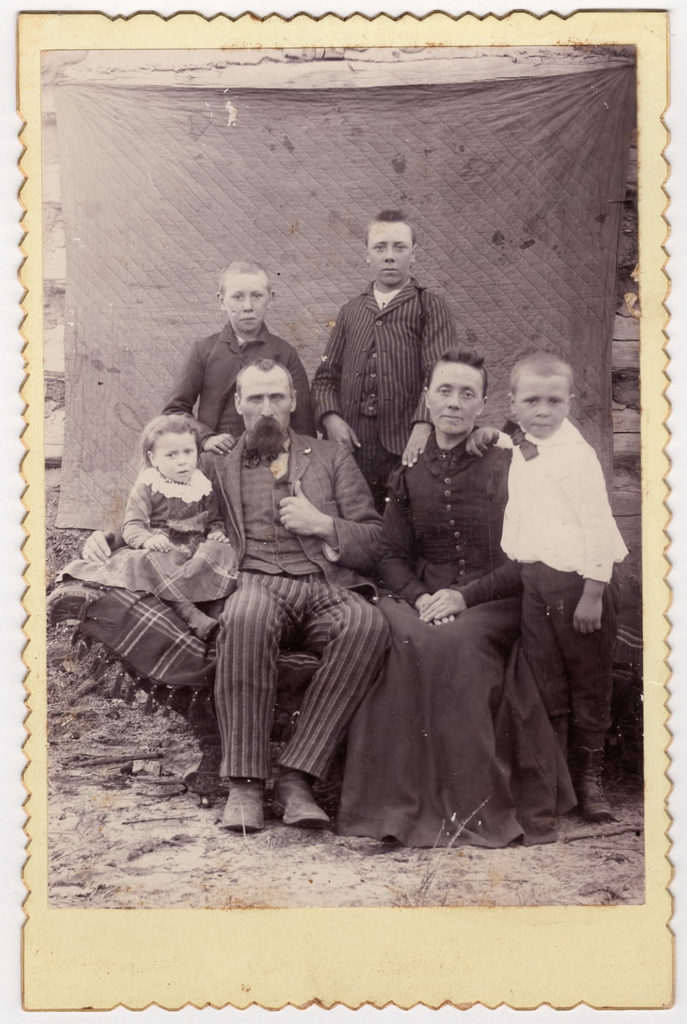

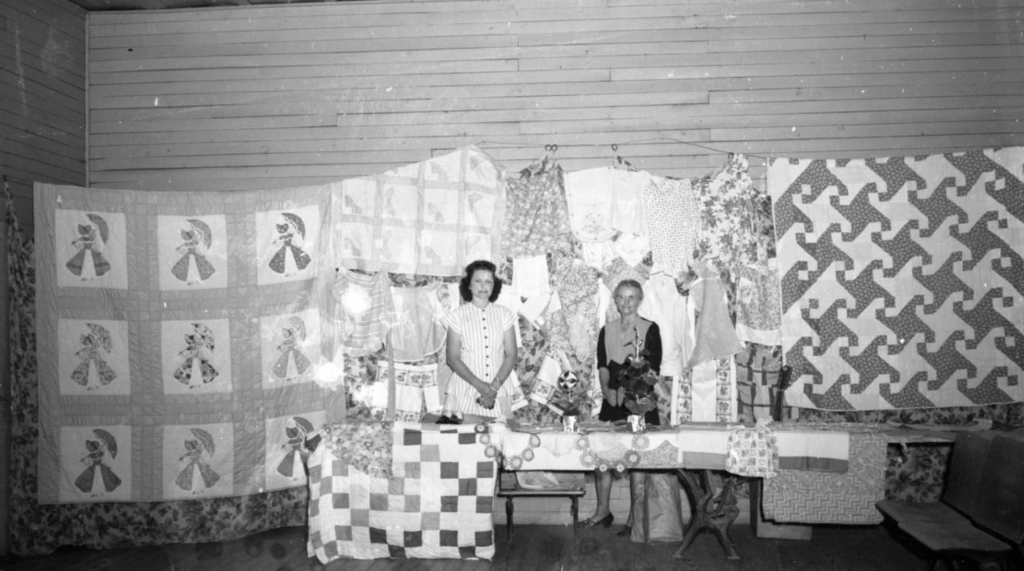

Here’s a photo of my great aunt and my great, great aunt, posing before their booth at a church bizarre in East Texas. It’s most likely that they didn’t sign those quilts. Why not?

Collectors of vintage and antique quilts are a passionate bunch. There’s a subset among us—historians—who spend a lot of time researching the makers of signed quilts, to make them known. I’m thankful for their work and encourage you all to go see a really beautiful exhibit at the Tennessee State Museum right now with some great examples of signed quilts important to the heritage of Tennessee.

But for myself, while I’m always happy to acquire a signed quilt, the anonymity of most vintage and antique quilts is inescapable. It’s that anonymity that inspires my imagination.

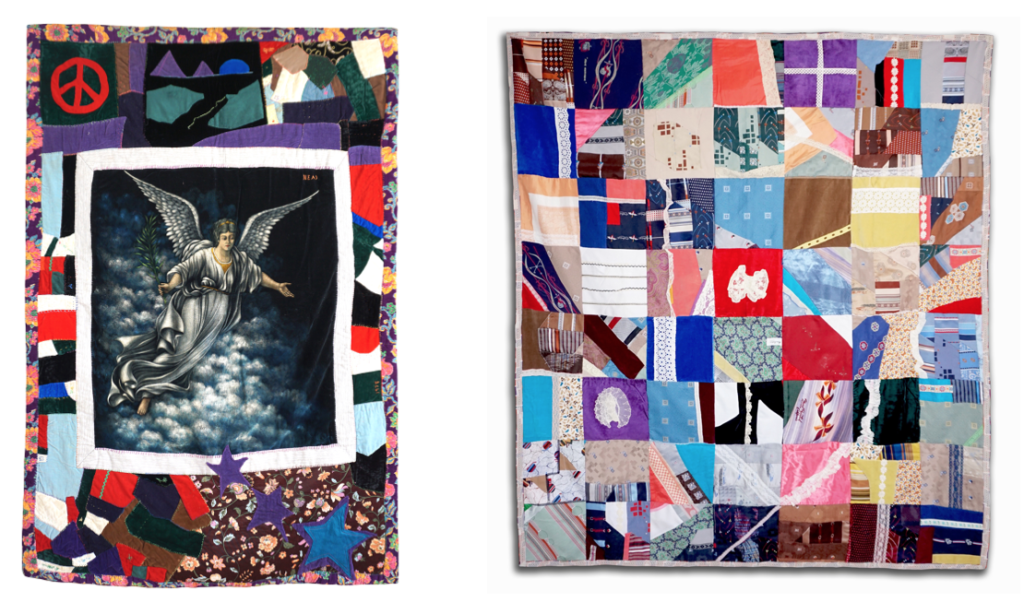

Here are two quilts that are obviously the product of both vision and ambition. On the left, a clear original, thought out and intentional, and unsigned.

On the right, a rare example, circa 1920-1930, of a bulls eye quilt. Found in Rhode Island, the small number of similar bullseye quilts we know of originated in two different eras from Lenhartsville, PA. It took an amazing amount of skill to make this quilt. It’s unarguably a masterpiece. No one knows who made it. And that is not uncommon.

In essence, the lack of signage in American quilts has created a collective body of women’s creative work, it’s our heritage. And it’s this that I am most interested in.

Let me digress into probably familiar territory for many of you.

I’ve noticed a lot of debate over the years about whether vintage and antique quilts should be considered art. I don’t think that’s a big debate here, but for some reason, in other circles, it’s debatable, so thought I’d mention it.

It’s clear to me that the quilt, a domestic material object made and used for warmth, was and continues to also be a canvas for creative expression by women, who have made incredible use of it.

Much of the debate about whether quilts are art seems oriented toward convincing “the art world” to hang quilts on art museum walls. It’s a worthy pursuit that I won’t knock. They do belong there. And I do treat my quilts as art, hanging them on wall.

When I was invited to present a special exhibit, I spent some time thinking through how I might want to narrow my collection to one set, coming up with various ideas based on time period, fabric, techniques etc.

Ultimately, I wanted to bring quilts that would inspire today’s modern quilters, that was my first criteria.

The end result was a group that spans time, geography, technique and fabric, and obvious socio-economic strata. What they all have in common is strong design—from explicit compositional choices to sophisticated combinations of color and shape.

Here are two favorites that I often have on the wall in the spring.

On the left is a classic oversized courthouse step quilt, made mid-century with that lovely Baptist Fan stitching.

On the right, same era more or less, is a stunning example of what I call a structured improvised patchwork, made from some of the earliest synthetic fabric.

The artistry demonstrated historically by quiltmakers is very clear, the high geometry, the sophisticated choices of shape, color, scale, both realist and abstract depictions of the natural world.

It’s tantalizing, a great past-time actually, to speculate about how the quiltmaker intended her quilt to be viewed.

All this said, I don’t find the conversation about quilts as art all that resonant when the conversation is divorced from the context of the lived reality of women’s lives.

Let’s face it, the road to women’s equality is a long, and ongoing one. My collection spans several social movements for women’s equality. Those movements sought to open up public spaces to women—among other things, the right to vote, the right to not be wards of their husbands or fathers, to access jobs, government and academic positions, to pursue autonomous and creative lives.

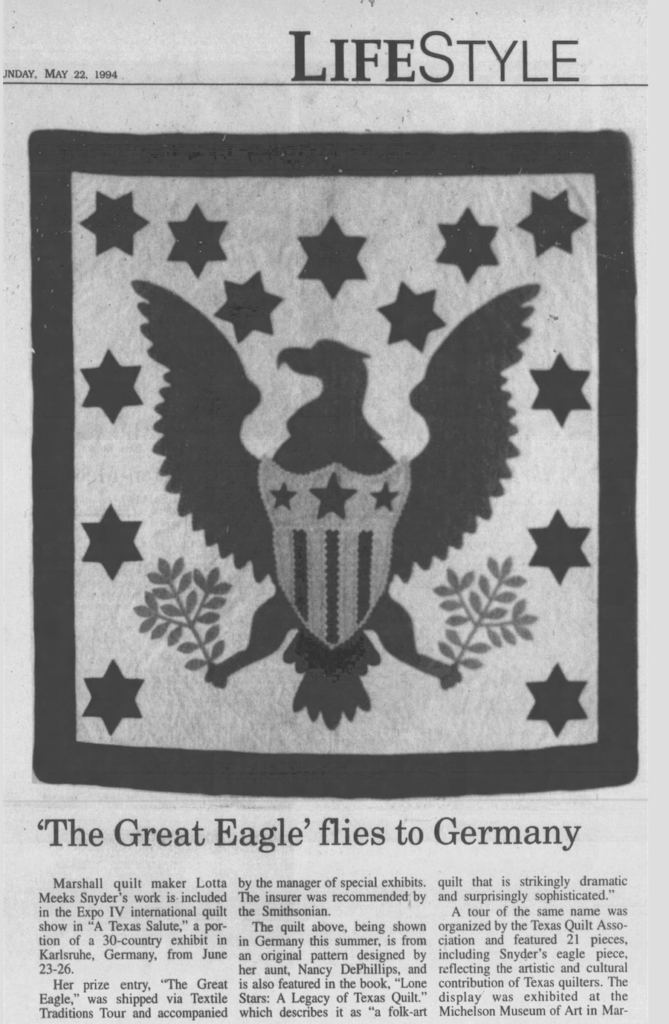

The quilts I brought this week don’t include album quilts, But I want to show you this one.

Made in the 1970s, it memorializes the women’s movement of that era. The women who made it were in a southern California applique class, much like the workshops many of you are taking here at Quiltcon. The theme was, simply, women. The blocks depict women doing both traditional “women’s work” as well as men’s work, one a linesman and one a carpenter. And of course, the women who made the top were engaged in traditional women’s work, part of an embracing, so to speak, of women’s work, in a decade now referred to as the great quilt revival.

You can read more about this top in the book Quilts and Human Rights, published by the U. of Nebraska Press.

The quilt top tells a story, doesn’t it? Story telling is just one of the many past times that women have pursued through quilt making.

They’ve made them to raise money for important causes, to express their love for someone, to build community, to both compete and collaborate with one another, to demonstrate their skills.

It’s within the full context of the intersection of quilts and women’s lives that I find the artistry of quilts so resonant.

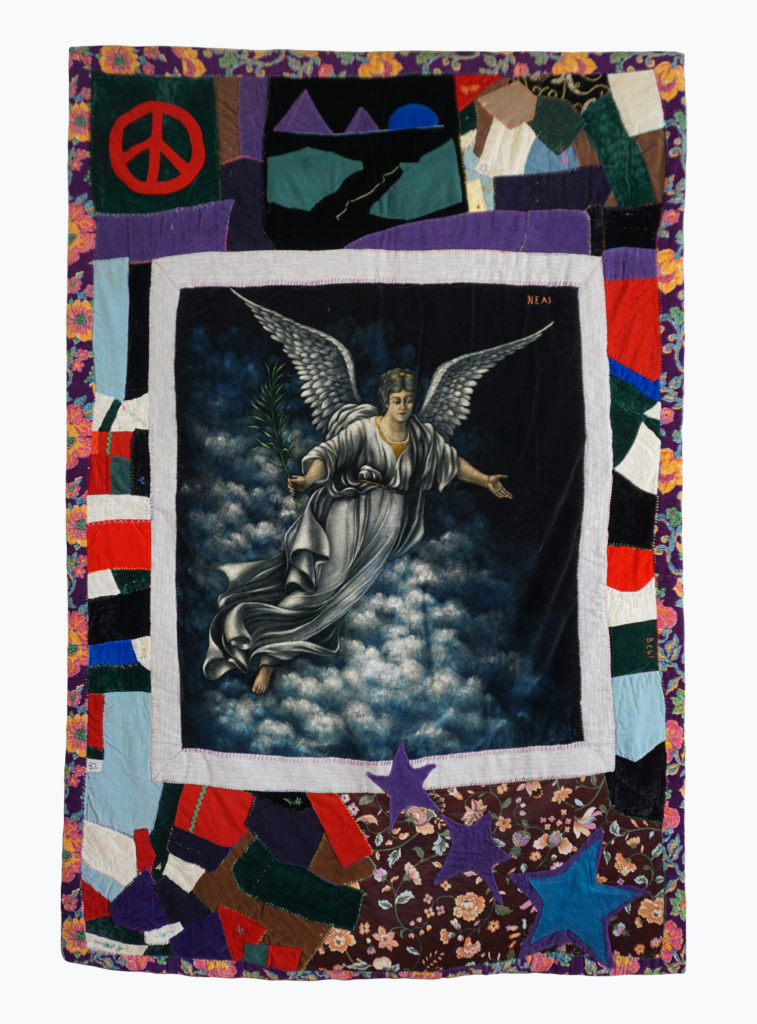

Sometimes a quilt is an artifact of a family, a remembrance. Consider these two quilts.

On the left, a quilt that is strikingly evocative of remembering a loved one, with the classic velvet angel in the center, the Peace sign, and a name embroidered right on the angel – Neil. Near the top is a small patch that says “Male”, the type you’d see put on a denim jacket.

On the right, a quilt composed of men’s ties and crochet. Each block is meticulously designed. Perhaps a daughter made this quilt to remember her parents. We can’t know, because it’s anonymous. But it’s strongly resonant of memory.

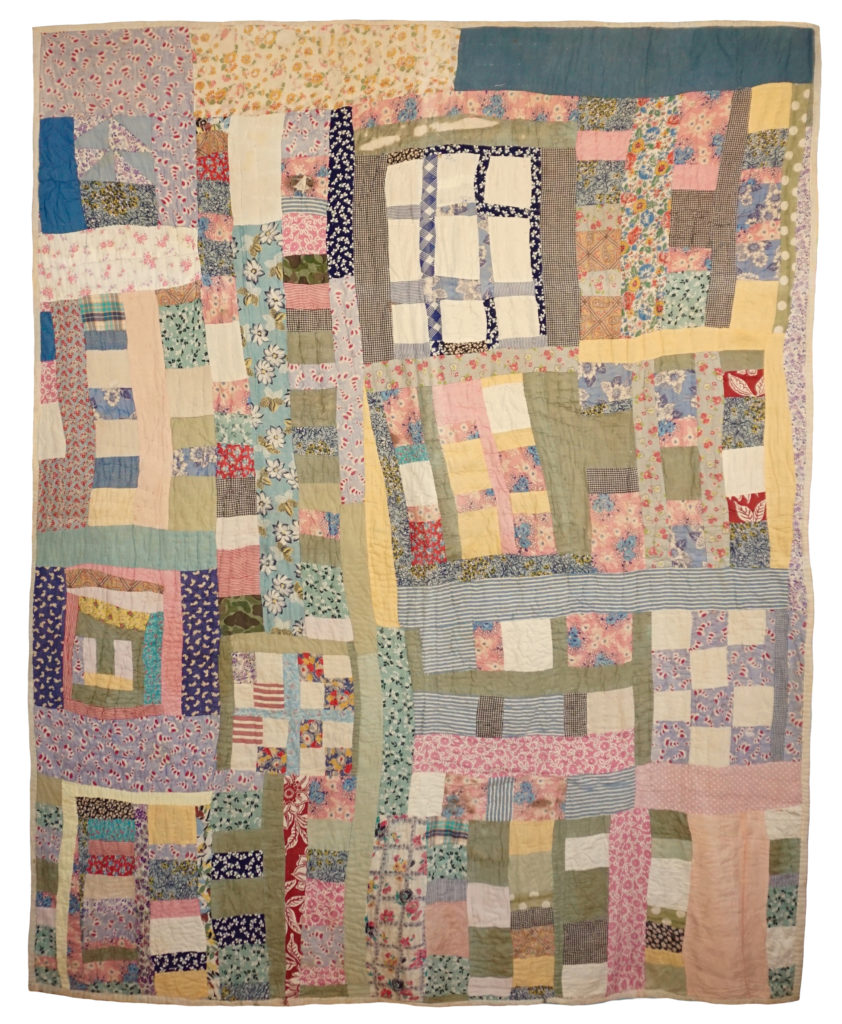

And sometimes a quilt was just a quilt, meant for warmth. Even if today we treat it as art.

On the left, a turn-of-the-century wool patchwork, made for warmth. The back is a rustic rich home-dyed blue. What really sets this quilt apart, maybe why it was saved so well, are the dense, long ties that add incredible texture. It must have been lovely on a bed.

Who knows what sort of quilt is on the right?

It’s a Southern Linsey, made from a rough, plain homespun weave of wool and cotton, most likely originating from the southern United States, circa 1870. Believe it or not the rough fabric was used in clothing. This quilt was likely made of cast-off clothing, while the back is made of two striped panels of the homespun fabric. Dyed rich earthy colors with a great tonal quality, it’s simply a beautiful and important piece of our heritage. To learn more about these quilts, I recommend the work of Merikay Waldvogel, a quilt historian from right here in Tennessee.

Let me show you a few more quilts and then we’ll open up the floor for comments or questions.

Sally Bachman, who made the quilt on the left in 1881, was very interested in demonstrating high skill. When I first saw the quilt, I loved the off-center placement, so bought the quilt. But I suspect that appreciation is just a sign of my modern sensibility, not necessarily how she meant it. The off-centered focal point could have been a mistake, or it’s possible it’s made to fit a particular bed.

It’s important when contemplating the art of quilts to remember we don’t know the intentions of the quiltmaker. The great majority of quilts were meant to be placed on beds, I encourage you all to have a look at them in that way if you are primarily in the habit of hanging them on your wall. The amazing pop art geometry of your favorite will take on a new dimension.

This log cabin quilt is a good example. A one of a kind design in a classic genre, it’s one of the first I ever purchased and I used to hang it on my wall a lot when I lived in a bigger space. Then one day I put it over my bed, and the clear lines that run through it were even more striking if you can believe that.

~End~

My goal of inspiring modern quilters was met. Here are a few Instagram posts that show more of my quilts that were displayed:

And here are a few of my Instagram posts: